A Thousand Words About Kevin

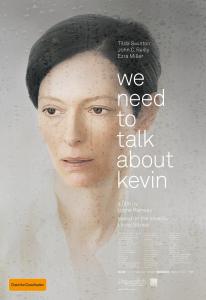

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. I would dispute that, based on some of the films that have recently been adapted from books. A good example is the film version of Lionel Shriver’s book We Need To Talk About Kevin.

It is said that a picture is worth a thousand words. I would dispute that, based on some of the films that have recently been adapted from books. A good example is the film version of Lionel Shriver’s book We Need To Talk About Kevin.

In the book, the story is narrated by Eva Katchadourian whose teenage son Kevin has committed a terrible crime. Through a series of letters, Eva relates the events leading up to this crime. In so doing, she goes into great detail about Kevin’s upbringing. But there is also a back story in which she speaks at length about her own career as a publisher of travel books and about her relationship with her husband. This provides vital context to the main plot. In the film version, this back story has almost entirely vanished.

We Need To Talk About Kevin is a good film in its own right. It is fairly well made. It is perfectly cast and well acted. But without the context provided by the back story, it seems strangely flat to someone who has read the book. It is, to borrow a line from Paul Keating, ‘all tip and no iceberg.’

It’s well known that film and literature are two very different mediums. It would be naive to think that the psychological depths of a novel like this can be captured in a two hour film. A novel is not written with the expectation that it must be read at a single sitting, so it can waffle on for hundreds of pages. A film has to tell the same story in a couple of hours. A novel is considered successful if it reaches, say, ten thousand readers. A film, being much more expensive to make, will bomb financially unless it reaches at least ten times that number. So the film is constrained not only by length but by the need to appeal to people who may not have the time, patience, or concentration to read novels in the first place.

On reflection, it’s surprising to realize just how limited film can be as a storytelling medium compared to the novel. In fact, the old line about a picture being worth a thousand words can be thrown away as a myth! It’s not that We Need To Talk About Kevin is a shallow film, it is that the psychological depths of the story are forever out of shot. The viewer who has not read the book could just as well watch the film and make up his or her own back story as to why the characters acted as they did.

A pivotal point in the book is Eva’s chronic ambivalence about the idea of motherhood. She wavered for months, or even years, on whether it was a good idea to disrupt the happy life she shared with her husband Franklin by having a child. Her thriving career as a travel publisher would also be threatened, and was in fact effectively ruined after she became pregnant. This career is discussed in some detail in the book but almost never in the film. It is exactly this ambivalence about motherhood which helped the novel become a bestseller with the female readers who make up a large part of the book-buying public. Yet it was barely mentioned in the film.

One interpretation of the book is that Kevin turns out evil because he’s a projection of the part of the mother that never wanted the child and resents his existence. But as this theme is never explored in the film, it is little wonder that the film feels flat. Tellingly, the final scene in the film is one in which Eva asks Kevin why he committed the crime, and he admits that he doesn’t really know. This comment probably sums up the film itself and the thoughts of the viewer. It’s interesting that this scene is not in the book.

The problem with the movie is that no real reason or explanation is given for why Kevin would act as he did. He therefore becomes a one-dimensional villain; a stock ‘evil child’ with about as much psychological depth as Damien from The Omen movies, or the little girl possessed by the devil in The Exorcist. He’s no longer the interestingly-evil character that he is in the book, he’s just a cartoon black haired demonic child.

Likewise, the movie version of Franklin, the husband, has no depth at all. In the book, his character is given considerable substance. He’s presented kindly as a man with heartfelt belief in the best of American ideals, and if he comes off as naive and ultimately as a bit of a dork, the reader can at least feel some sympathy with him. In the movie, he simply wanders on screen from time to time, fails to notice Kevin being evil, and wanders off again. There is no indication of why he was even attracted to Eva in the first place, and his views and ideals are rarely explored. This is not the fault of the actors, nor perhaps even the writers, but rather shows what a weak and limited medium film can sometimes be compared to literature.

In the book, for example, Eva explains how and why she detested the ‘dream house’ Franklin bought for them while she was on one of her work trips overseas. In the film, it is not mentioned.

Another key point of the book is the contrast between Franklin and Kevin. Franklin still holds dear some kind of apple-pie-and-baseball 1950s idealisation of America. Kevin, by his thoughts and actions, represents a nihilistic, amoral rejection of all that. As with motherhood itself, Eva has a strong ambivalence about her husband and his worldview. Eva the aloof, expatriate cynic is both charmed and repulsed by her husband’s idealized love for America. Part of her yearns for the warmth and simplicity of his worldview and tries to embrace it. Yet in giving birth to Kevin, she comes face to face with a monstrous embodiment of her own cynicism and negativity, which ultimately destroys her.

Most of these psychological depths are lost in the film version. Or at least that is how I see it after a single viewing. If I watch the film again, perhaps these themes will come through more strongly. I doubt they will be strong enough to change my view on the limitations of film as a medium for adapting novels. If you’re happy to see the tip of the iceberg, go watch a film. If you have the time and inclination to look at the actual iceberg rather than just the tip, then take the time to read the book first.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.