A Horror Story With No Apparent Foe

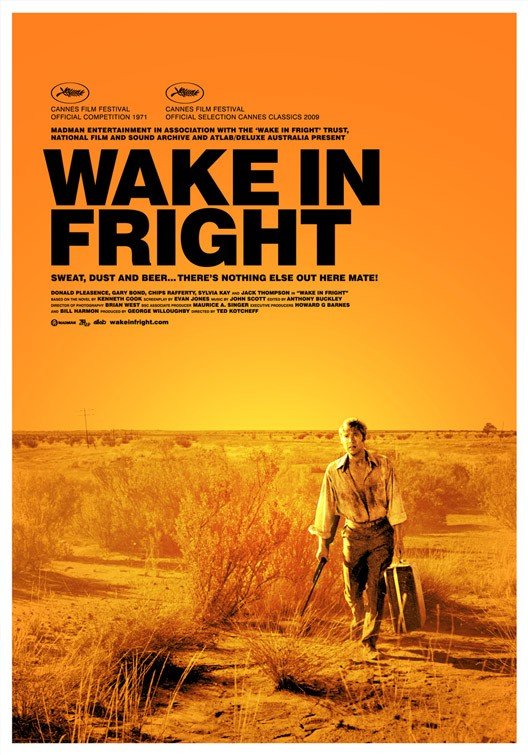

A nightmare is usually something you wake up from with a sense of relief. For John Grant the ‘nightmare’ is something he awakens into, in a state of dread, each morning for five days. Hence the title, Wake In Fright, of a brilliant 1960 novel by Kenneth Cook, which was made into an equally good film in 1970.

Wake in Fright is a horror story with no apparent foe. There are no ghosts or demons, no serial killers, no predatory animals or aliens. It’s far more subtle than that. The sense of dread is barely noticeable at first, but steadily grows. The ‘enemy’ as it turns out is the environment itself, its strangely savage inhabitants, and the protagonist’s fear which binds him there.

John Grant is a sensitive, intellectual school teacher from the city. He describes himself as a ‘bonded slave of the education department.’ This refers to an actual policy of the time in which teachers had to complete a two year apprenticeship in the bush before being allowed to work in the city. Teachers had to post a bond of $1000, which was forfeited if they skipped out on the deal. $1000 was a lot of money in 1960.

John Grant has been assigned to Tiboonda, a tiny one-school town in the outback. He’s just finished the ordeal of his first year. This is at the height of summer in what is essentially a desert. It is a cultural as well as a physical desert. As a phrase from the movie puts it, ‘there’s nothing out here except heat, dust and beer.’ For the aesthetic Grant, Tiboonda is a place to be viewed with horrified incredulity. It can be kept at arm’s length by Grant’s retention of his own identity, and endured through the knowledge it is only temporary. He’s been kept sane by the thought of his six weeks annual holiday coming up in Sydney. As he boards the train at the end of term, he’s tantalised by dreamlike visions of water; breaking waves at Bondi Beach and his bikini-clad fiancée among them.

These images turn out to be desert mirages for Grant never escapes. He’s booked a stopover at a larger town named Bundanyabba, staying there one night before catching his flight back to Sydney in the morning. In a holiday mood, Grant goes out for a beer to kill time. In a local bar he meets Jock Crawford, the town cop, one of the ‘devils in human form’ of this story. Crawford, with no apparent effort or plan, puts the twin demons of alcohol and gambling within Grant’s reach. There’s reason to think these vices are not native to Grant. Indeed he looks on condescendingly as the locals engage in them. Yet Crawford somehow gets Grant to down a few beers, before taking him to a Two Up game. By story’s end, Crawford hints at a quiet satisfaction in Grant’s debasement.

Grant is soon drunk enough to have a go at the Two Up. Sure enough he wins three times in a row and triples his holiday pay. Whooping it up he runs off to his hotel room before the devil within plants an idea in his head: one more win will give him enough money to pay off the teacher’s bond so he won’t have to return to Tiboonda for the second year, or indeed at all – ever. In the grip of this wild hope, he returns to the game and of course loses all his money on the next play. He no longer even has his fare for the plane home. (I assume that in 1960, there were no prepaid bookings!) He stumbles off to bed, then wakes the next morning in a strange hotel room, naked, penniless, baking in the desert heat, with the hungover from Hell and the knowledge he now has no means of escape.

As a personal aside, perhaps this story resonates with me because I once found myself in a similar position. I was moving from Sydney to Adelaide, driving the 1000km journey with all my worldly possessions in my car. Speeding recklessly at the end of a long day outside a godforsaken small town called Hay, I crashed and rolled the car. I woke up the next morning in a strange hotel room, at the height of summer with no car, virtually broke, shattered and disoriented. I vividly recall the desert landscape, the heat, the fear, the sense of having been stripped of power, and being trapped in a remote Australian town.

John Grant’s nightmare has now begun. He’s stuck in Bundanyabba with no means of escape – but it’s not as if anyone is hostile to him. Here again is the strange subtlety of this film. In fact, the locals are aggressively hospitable, buying him endless rounds of beer, only getting offended when he asks them to stop.

‘New to the Yabba?’ he’s asked repeatedly. All the locals love the place John Grant despises, a fact that confounds him. ‘All the little devils are proud of hell,’ comments Doc Tydon, a cynical alcoholic doctor who Grant meets in a bar. Tydon’s ‘disease’ has prevented him working in the city, yet in Bundanyabba it is ‘barely noticed.’

It is Tydon who represents the greatest horror for Grant. Given to quoting philosophy and literature, Tydon has become a sort of educated beast, living in a squalid hut, permanently drunk, keeping a thin hold on the facade of civilisation. Grant is later taken on a drunken kangaroo hunt and sees Tydon cutting the balls off a dead roo, prizing them as a delicacy to be cooked and eaten later. This has added significance for a later event implied but not shown.

Doc Tydon has been all but absorbed into the hostile environment, slowly transformed into some kind of ‘talking pig.’ In John Grant’s waking nightmare, he sees this may be his own fate as well. Day by day, he realises his former self has evaporated into the desert heat. The only option is to surrender and become a beast himself. By the end of the five days, that is what he has become.

Wake in Fright, has no visible monsters: no ghosts, no sharks or serial killers. Even the humans are friendly to John Grant at every step of the way. At no time are they hostile to him. They’re all simply incidental devils living in the strange hell of Bundanyabba into which Grant has blundered.

The film could be said to caricature a certain kind of Australian masculinity, with its violence and drunken hedonism. But no, it is real, all too real. The story is filtered through the consciousness of the intellectual John Grant, a man who would be more at home in England’s ‘green and pleasant land,’ or walking the corridors of Oxford University. His waking nightmare is at the extreme end of a certain English perception of Australia and the Australian male, or a European’s perception of the outback. It is Grant’s own horror that has ensnared him, for without his desperate desire to escape the place, he’d never have risked losing the plane fare on so reckless a wager.

Money is power, its absence is slavery. For gamblers, the two sides of the ‘Two Up’ coin are not heads and tails, they are freedom and enslavement. Gambling is one of the demons of this nightmare. Alcohol is another. Beer is the same colour as sand. Beer is the liquid counterpart of the desert dust. In the end, it comes to the same thing. All drinkers know the ‘heat’ of dehydration and the futile illusion of drinking more to combat it.

This is all part of the awful brilliance of Wake In Fright. You can have your Evil Dead or Friday the Thirteenth. Real horror is to be found in the brutal banality of daily life with its harsh grind, its relentlessness, and the constant flux between hope and fear. Wake In Fright is the nightmare where the hope of escape tantalises again and again, only to vanish like a desert mirage and return you once more to your starting point. Forget twilight and midnight, real horror happens under the sun. So it is in this Australian classic.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.