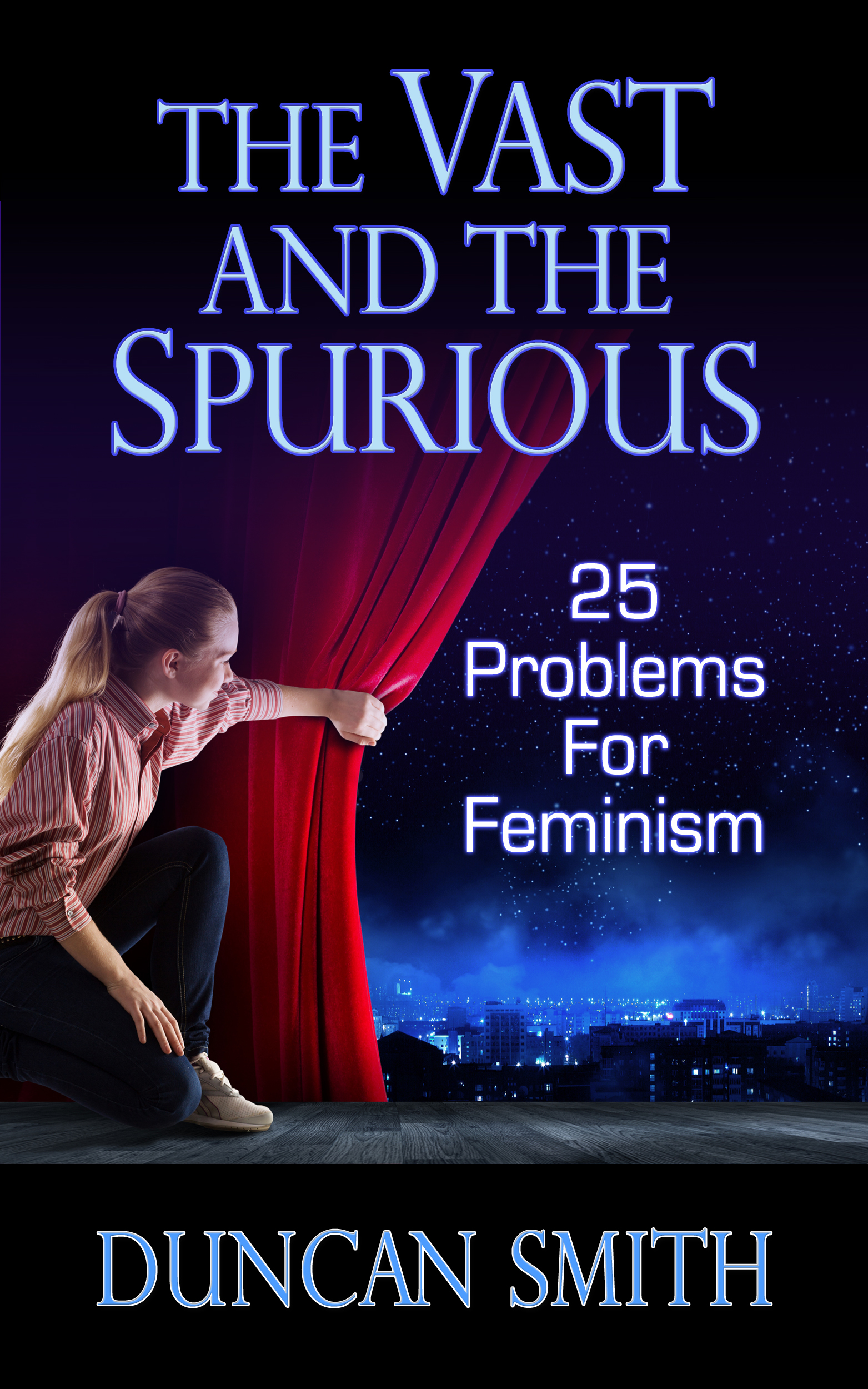

The Vast and the Spurious – chapter one

This is the first chapter of the book.

The Vast and the Spurious – Chapter One

This book discusses twenty-five problems with feminism. One of the main problems is you’re not allowed to criticise it in the first place. As I’m going to do so at some length, this will make me a target for attack. In that case, I’ll start by explaining my position and why this book has been written.

Some people think any critic of feminism must be a right wing thug who wants to send women back to the 1950s. But I believe women should have the same rights as men and be free to pursue any goal. Why shouldn’t they? Still, supporting the fair reforms of the 1970s doesn’t mean you have to endorse the cultish fanaticism that goes on today.

Of course, a movement as big as feminism doesn’t exist without reason. On some topics feminists are right, on others they are wrong. The aim of this book, The Vast and the Spurious, is to try to understand which ones. Where they are right, their efforts may lead to a better world. But where they are wrong, their mistakes will lead to a worse world – for everyone. #Feminism hurts women too.

I am male. For some, that disqualifies me from having an opinion on this subject. But as the modern agenda consists of hectoring men about their enormous power and privilege, it’s clear feminism is not just about women’s issues. They will accuse me of ‘man-splaining’ feminism, but as feminists have been woman-splaining for years how patriarchy ruined their lives, it’s only fair to return fire. Still, in deference to those who’ve gone before, let’s start with the ceremonial rites.

Acknowledging the Traditional Owners of The Land

As a man writing on this topic, I’d like to acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Gender Studies: feminists.

Apparently they own the land. They get very angry if a man trespasses on that land by having a voice, or even a thought, about gender issues. This anger may be cloaked in the pretence that they don’t care what men think. They will sometime declare, with passionate indifference, just how much they don’t care. Indeed, when it comes to feminist books, it seems to be a genre convention for authors to assert that they ‘don’t give a fuck’ what men think of their field. Clementine Ford says this in chapter eight of her book. Jessa Crispin says it in chapter seven of hers. Probably a hundred other women have said it in theirs.

This is really a wonderful liberation for a fellow like me, for when I began writing this book, an inner voice would often be nagging away about whether feminists would approve. It’s a great relief to learn that they don’t care what any man thinks.

Still, having entered the field of feminist writing, it’s only polite to observe the genre conventions with the ritual words: I don’t give a fuck what men think about feminism. There. Was that OK?

Now the formalities are over, let’s get on with the book.

A Few Points to Begin

To be honest, that was a lie. I do care what people think, and maybe this book can even change a few minds. Not the hardcore feminists, of course. That will never happen. But the book isn’t written for them. It is for the open-minded woman or man who wants to hear a different view than the media allows. It’s for the kid starting university about to be force-fed identity politics for the next three years. It’s for those sick of the one-sidedness of the conversation.

Still, before criticising feminism in detail, it’s worth remembering why it exists, and the sort of thing that fired women up in the seventies and sometimes still goes on today. For example, I recall one time from my own university days when a pompous male academic lectured for an hour, then also dominated the tute group that followed. We sure got sick of his voice. Then there was a recent YouTube clip where a young woman gave a brilliant performance on the bass guitar. One of the top comments was ‘the best part of this video is her smile.’ This retro chauvinism would easily make that Everyday Sexism website.

So, while this is mainly an anti-feminist book, it is sympathetic to them when they have a fair point. Apart from being a matter of ethical fair play, there’s more chance of changing people’s minds if you show some empathy rather than just trying to blast them into oblivion. They might then start to listen and empathise with you too. Of course, if that doesn’t work, you can always fall back on plan B, which is to blast them into oblivion.

In the same spirit, this book won’t be taking any cheap shots at the physical appearance of any feminists. That sort of personal attack is irrelevant, and reflects badly on the attacker. Behavioural ugliness on the other hand – such as lying, bullying, or slandering – will be called out whoever is doing it.

For the record, I support some of the basic feminist causes, such as equal pay for the same work and a fair deal on housework and parenting. Ironically, the only way feminists will ever actually solve those problems is to stop lying about the ‘gender pay gap.’ That is, lying about its real nature and causes.

As for whether males and females have the same innate abilities, let’s just say people should be treated as individuals, and get the benefit of the doubt until proven otherwise.

As for other issues, I support women’s right to sexual freedom and to not have to face blatant sexual harassment, but oppose the recent excesses of the Me Too movement.

Then there’s rape and domestic violence. It’s pretty obvious stuff, you would think. Domestic violence, for instance. You mean it’s wrong to beat up your own family? Who knew? But that applies whichever gender is doing it. Contrary to popular belief, it doesn’t just go one way.

What I chiefly oppose in feminism are some key delusions, some behavioural traits, and the overall mental climate these create. Among the main delusions are that woman are always worse off than men, and that men are always villains and women victims. Another problem is the fixation on gender where it has no relevance.

As for behaviour, I oppose the feminist attempt to leverage historical suffering for present day gain, and its culture of bullying and intimidation. The overall climate all this creates is one of hatred between the sexes. While this is not all the fault of feminists, they have certainly played their part.

Origins of this Book

This book was prompted by several events, of which two stand out. One was reading a newspaper article about ‘male privilege,’ which is the idea that men are better off than women in almost all areas of life. The implication was that men cruise through life as pampered lords, while women struggle through like the damned in Hades.

The other event happened when the book was already half written. It was the attempted screening in Australia of a film called The Red Pill, which gave a sympathetic hearing to Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs). This was an act of profanity for feminists, who protested and got the film banned. MRAs are those who challenge the feminist premise that women are always the disadvantaged sex. What’s striking about The Red Pill is it started out as a hit piece on MRAs, but its female filmmaker changed her mind once she got to know them. This was pure heresy for feminists, who called it a propaganda film. That was odd, because when I finally got to see the film, it turned out to be an alternative to the feminist propaganda we normally get in the media.

Really, The Red Pill just offered another view on gender relations, but the whole protest debacle shows there is something deeply wrong with feminism today. If the way you deal with critics is to silence them or lie about them, this is highly revealing about the sort of movement you are.

So, The Red Pill is ‘a propaganda film,’ is it? If by propaganda they mean someone’s opinion, then we are all propagandists. The difference is some people get to deliver their propaganda through national, mainstream media. Clementine Ford, for example, writes one or two newspaper columns a week – and while Ford is a formidable warrior for her cause, she only ever argues one side. Still, by all means read her columns and books. Then for the sake of balance, go and listen to a YouTube talk by Janice Fiamengo or Karen Straughan.

Karen Straughan is one of those evil Men’s Rights Activists you hear about. She’s popular with men due to her eccentric penchant for not hating their guts. I had actually never heard of MRAs when I began writing this book. Since then, and after watching The Red Pill, I’ve heard a good deal more about them.

Feminists need to move on from the idea that they have a monopoly on sorrow. Injustice takes various forms and is experienced by many types of people – even some of those white males they think are so privileged.

This book was originally two long essays. The first was called ‘Agony: Much More Painful Than Yours,’ (meant humorously, of course). It looked at twelve problems to do with the idea of male privilege. The second essay, ‘The Vast and the Spurious,’ looked at a further twelve problems.

I’ve kept those original ‘problems’ and spread them out over the chapters of the book. Some are dealt with briefly, others at much greater length. ‘Problem 25’ will make up the last chapter.

In fact, some of these are problems for feminism, not problems with feminism. For example, problems 12-14 are sympathetic to them. Here is a full list, with the names I’ve given them.

- Trump or the Tramp

- The CEO Problem: Check Explanation, OK

- It’s Not 1970 Anymore

- Female Privilege

- Agony: Much Worse Than Yours

- We Are Not a Gestalt

- Gender Doesn’t Matter

- How Dare You Resist My Attack?

- Big Sister is Watching You

- Misogyny vs. Misandry

- The Gender Pay Gap

- Yes, That’s Annoying

- The Weight of History

- Dickheads Anonymous

- It’s Still Not 1970

- What Ya Gonna Do?

- Bullshit or Not?

- Whinge, Whine, WTF

- So Fucking What?

- Stop Caring What People Think

- Assert Yourself or Die

- Do Something

- Give Me My Privilege!

- Turning Male Problems into Male Privilege

- Addicted to Feminism

Apart from these twenty-five problems, the book has five main parts. Chapters 2-4 are about male privilege. Chapters 5-8 discuss the capacity for evil in both men and women, and respond to a feminist’s attack on MRAs. Chapters 9-12 deal with the gender pay gap, and the battle over work in and outside the home. Chapters 13-17 return to male privilege. Then, chapters 18 and 19 complete the book, and include the Utopian vision, ‘A Dream of Fecunda.’

It’s worth noting that this book is about Western nations, and does not discuss feminism or the position of women outside the West.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.